Nostalgia creeps up on us all as part of the ageing process – the belief that the old ways were for the best. But memory is notoriously fickle. Guest author, Tom Bruce Gardyne reflects on The Old Ways of the past.

As the whisky writer Dave Broom once put it – “Summers were always sunny, it always snowed at Christmas, and Partick Thistle won more games than they lost. How devastating it is to find out all of that might not have been true.”

At House of Hazelwood, one area Charles Gordon (of whom The Charles Gordon Collection is eponymously named) almost certainly had no nostalgia for was the feudal nature of the industry he joined in the early 1950s. As the great grandson of William Grant, his efforts to grow the company were stifled by the giant Distillers Co. (DCL) who controlled most of Scotland’s grain whisky production. There would be annual negotiations on how much of it, DCL was prepared to swap in return for casks of malt whisky, to allow the wider whisky company to produce its popular blend.

At some point Charles, then joint-MD, was told the supply was to be cut back. This confirmed his suspicion that DCL thought the whisky business had grown too big for its boots, and strengthened his resolve to break free from this overbearing supplier, and build the company its very own grain distillery. Having scoured Scotland for possible locations, Girvan on the Ayrshire coast was picked in early 1963. “The first bulldozer hit the Girvan site on April 14th,” wrote Magnus Magnusson in Focus magazine a year later. “The first brick on the levelled site was laid in August. Yet by the end of December, the first run of whisky was flowing and Grant’s new grain distillery was in business.”

It was a massive undertaking, and to pull it off in just nine months was incredible. “It involved 400 men working day and night, in often atrocious weather, spurred on by the lure of more overtime and yet more whisky. “There’s a bottle in it for each of you if you can finish the job by midnight,” was Charles’ constant refrain as his toured the site on his bicycle, having moved into a caravan on site in mid-October.

The drive to get it finished by Christmas was “part emotional and part business,” says House of Hazelwood archivist, Andy Fairgrieve. “It’s obviously an important milestone in the company history, given that the selling season for grain whisky started in January.” Those who built Girvan celebrated with more whisky and by welding Charles Gordon’s bike to the highest part of the building recalls Dennis McBain, his occasional chauffeur and long-serving coppersmith at the company.

And so, to ‘The Old Ways’, a single cask single grain whisky from Girvan in 1972. Its name would have puzzled the people who distilled it when Girvan was the most modern distillery in Scotland and positively space-age compared to many. But undoubtedly things have changed, starting with the grain itself. “Today we use wheat, while in 1972 it was maize,” says the company’s Technical Leader, John Ross. “It was called old red maize number two corn, and it was brought in by the boatload from the USA.”

Today, perhaps the greatest difference in grain whisky production stems from the stills. In the 1970s Girvan and others were using an updated version of the Coffey still, patented by Aeneas Coffey in 1830.

At Girvan they were known as No.1 and No.3 Apps – and were “made from 100% copper” says John who later became the distillery’s production manager and installed the world’s first multi-pressure process for grain whisky. “The level of control today is astronomical compared to what it was in 1972 when you had to rely very much on the stillman. He would listen to what was happening and could tell by the pitch of the steam going into the still, and by taking samples and nosing them.”

It was more hands-on, more artisan, in other words and the spirit was noticeably heavier and more robust thanks to those stills and the maize. And compared to today, they would have used a bit more malted barley which is needed to provide enzymes to break up the starch in the grain. But for any whisky that has spent five decades in cask like this one, the wood is bound to play the biggest role. Just think of all those years of concentrating the flavours, adding complexity and depth and slowly bringing the whisky to its peak.

There is undoubtedly an element of serendipity in this, for what was distilled in 1972 at Girvan was never destined to survive this long. Although as John Ross points out: “You’ve got thousands upon thousands of casks in racked warehouses that are huge. I think it would be fairly easy to have missed one.” Added to which, there’s the whole ethos of the Gordon family to consider. “As a family business they can project for the long-term and lay down casks accordingly, whether it be for 30, 40 or even 50 years,” he says.

That takes some commitment given all the money tied up in stock, and all that evaporates into thin air as the angel’s share while what remains slowly loses strength. This is checked regularly along with the whisky’s quality and development in older, rarer casks, to ensure none have slipped below the 40% abv threshold to be Scotch whisky. The Old Ways has “obviously been in a place in the warehouse that was particularly cold and dark to retain its strength,” reckons John. That much is luck and being paired to such a fine cask in the first place, but the rest comes down to patience.

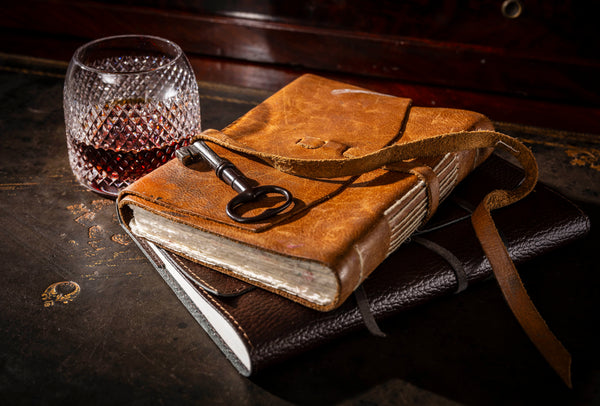

The Old Ways conjures up nostalgia and not just in name. As you nose its aromatic oiliness there is something in this whisky that stirs memories of old wax jackets and camping gas burners, coupled with a little Muscovado sugar. And that sweetness bursts through on the tongue with a medley of fresh and stewed fruit.

Discover The Old Ways, a 1972 Vintage Single Grain Scotch Whisky.