Once heralded the whisky of choice by connoisseurs and casual drinkers alike, why did Grain Scotch Whisky fall out of favour? We explore the reasons for Grain Whisky's downturn – and why it is now making a timely comeback.

When envisioning a Scotch whisky distillery, the brutalist appearance of a grain distillery rarely comes to mind. Industrial behemoths of scale, Scotland’s largest producers of grain distillery are themselves the size of a moderate town – some so large in themselves, that operators have had no option but to set up their own transport infrastructure to allow whisky makers to efficiently move from A to B.

Today, single malt Scotch whisky is the apple of many an afficionado’s eye – but this was not always the case. In fact, despite the buzz and hubbub of advocates heralding the good news of malts, grain distilleries remain integral to the performance of the industry. These towering giants are responsible for supplying the volume needed to export mainstream blended Scotch at a global scale - of which, despite the vocal preference of many- continues to hugely outstrip single malts in demand by quite a significant margin.

The sum of a grain distillery is more than its export – with the sheer size and scale of such an operation, these distilleries have over time established robust communities, supporting local economies with reliable employment for decades, partnering in agriculture with the distillation by-product of draff feeding livestock throughout Scotland and more recently, embarked upon sustainability efforts through supply of waste material for use within biomass and biogas plants.

Grain Scotch whisky – what’s the difference?

There are several differences in the production of grain whisky, but the biggest difference between a grain and a malt distillery undoubtedly lies in size – with larger grain distilleries producing tens of millions more in litres of alcohol a year.

The raw materials are considerably more flexible than the rigorous legal confines of malt whisky, with malted barley forming just a portion, rather than the entirety, of the grain used to distil. Instead, a combination of cereals is used to distil, including wheat, corn, maize, and rye.

The way new make spirit for grain Scotch whisky is produced is also different. To accommodate such a significant volume of new make spirit in production, distilleries will typically employ the use of continuous distillation through column (also known as Patent or Coffey) stills, versus that of a malt distillery that is more likely to distil in batches, using the more readily recognisable copper pot stills.

In layman terms, continuous distillation involves the act of constantly reheating the liquid within, passing vapours through stacked, heated plates in a tall, cylindrical still at various temperature points to enable condensation, forming the new make spirit. This style of production yields new make spirit at a much higher alcohol by volume (ABV) level than a pot still can.

The resulting new make, depending on the grain components used as raw materials, is distinctly sweeter than its malted counterpart. Like malt whisky new make, this spirit is subject to the same period of maturation in casks before legally evolving into Scotch whisky, where it is then either blended into blended or blended grain Scotch whisky or bottled as a single grain Scotch whisky.

Why did grain Scotch whisky fall out of favour?

Perhaps the biggest flavour myth of the late 20th and early 21st century is the rise in perception the single malt being of superior taste and quality in comparison to grain or blended Scotch whisky with the rise of malt Scotch popularity.

Single malts have only in recent years grew in popularity – as recently as the late 1960s - and although many distilleries have undoubtedly been producing single malt for far longer, blended Scotch and grain whisky were the amber drops of choice for decades before.

As whisky drinkers have rightfully sought out transparency from their favourite malt distilleries, a narrative has arisen that suggests due to the volume of alcohol produced at a grain distillery, there is a loss of romance or “craft” due to the factory-like nature of production.

This is ill-aided by the fact that much of new make grain spirit is truthfully destined for cheap, budget friendly blends – but to silo grain Scotch whisky in this way would be a missed opportunity to explore the merits of flavour that can present when balanced and overseen by a skilled blender.

The good news is that attitudes are changing – and appreciation for well crafted blended and grain whisky is on the rise, with the use of continuous distillation celebrated as a merit for grain whisky.

For instance, higher ABVs mean grain whisky can be matured for longer, yielding the opportunity to sample well aged liquid that would be otherwise unachievable due to the Angel’s Share decimating malt new make spirit of lower alcohol levels through evaporation.

This enduring property presents interesting potential from the perspective of cask maturation, with new make possessing the ability to lie comfortably in cask for half a decade or more. Continuous distillation alludes to a lighter new make spirit, increasing the influence that a cask could have on the final spirit.

To see this potential in action, we need look no further than from within the House of Hazelwood inventory.

The Cask Trials: The Chameleon of Single Grain

The Cask Trials, A 1968 Sherry Cask Vintage Single Grain is the ideal ambassador for the potential a Girvan grain whisky can offer. Having laid within a single sherry butt for 53 years, this expression could have been easily overpowered without the right guiding hand from the whisky maker.

Instead, the resulting spirit is rich and compelling, displaying a depth of character that if tasted blind, could fool the sampler into believing it is a greatly aged malt. Almost viscous in mouthfeel, the characteristics of a well-aged whisky are all there – from dried fruits, through to roasted coffee and Muscavado toffee.

Bottled at a cask strength of 49.2% ABV, it is rare that such an outstanding example of whisky, never mind malt or grain, comes along – and with just 303 bottles available, it is unlikely to be around for very long at all.

The Eight Grain: Grain History, Bottled

Production methods across grain distilleries may be similar, but the diversity in signature style across distilleries is as individual as comparing a Speyside Scotch to a whisky from Islay.

The Eight Grain, a 40-Year-Old Blended Grain Scotch Whisky, is a celebration of eight of Scotland’s closed and active distilleries, some of which will never be tasted again. The embodiment of its raw materials, this whisky demonstrates the sensational sweetness of grain through refined notes of baked sugar, caramelised banana, banoffee pie, and stone fruits offset with just a hint of wood shavings.

An unrepeatable example of Scotland’s very best, just 384 bottles of this expression are left to enjoy.

A Singular Blend: Transcending Styles of Whisky

In a landscape where those will heavily debate the argument of Grain Versus Malt, A Singular Blend, a 1963 Blended Scotch Whisky, offers an unexpected answer in the prevalence of distillery character, through both malt and grain component.

With both malt and grain elements distilled at the same distillery, in the same year, A Singular Blend is unprecedented in age and provenance, proving that each component can represent their distillery of origin in their own stead, regardless of raw material used.

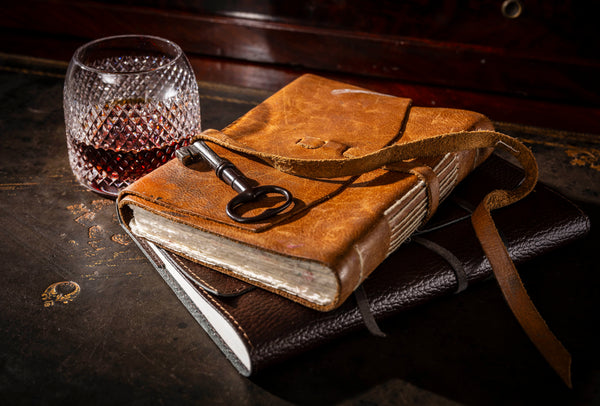

The resulting liquid offers an irresistible butterscotch sweetness, with a hint of saddlery workshops on the nose, followed by an open palate of beautifully balance sweet and sour, redolent of waxy fruit skin.

A remarkable bottling, with just 74 bottles available to enjoy.

Grain Scotch whisky – an underappreciated world of flavour

Of course, three, albeit outstanding, examples of Blended and Grain Scotch whisky cannot demonstrate the breadth of flavour potential offered by this style of whisky – but perhaps it will be enough to entice a palate of curiosity through the House of Hazelwood range.